Kai Matsumiya is the winner of the second annual Gramercy International Prize, and will be presenting work by Brazilian artist Pedro Wirz at The Armory Show 2020. The Armory Show spoke with both Kai and Pedro about their plans for the fair, and the importance of emerging galleries in NYC today. — Interview by Ellie Clark and Molly Krause

Ellie Clark: The Gramercy International Prize was initiated by The Armory Show in 2019, during the 25th Anniversary of the fair, to support the advancement of young and pioneering New York galleries. The Armory Show was originally launched in 1994 by four New York gallerists—Colin de Land, Pat Hearn, Matthew Marks, and Paul Morris—as a grassroots effort to support and celebrate the avant-garde. To honor this legacy, the Gramercy International Prize winner is selected, in part, for their embodiment of the spirit of the fair’s founders. How do you see yourself as continuing this legacy?

Philip Metten installation at Kai Matsumiya, 2015. Photo courtesy of Kai Matsumiya.

Kai Matsumiya: We live in a different time and circumstance than when the Gramercy International Art Fair first originated. It’s maybe even hard to spell out what “avant-garde” means today. There’s a recurring joke about how the “avant-garde went back to the military,” but this strikes me as too cynical, as I do believe that the pursuit of the avant-garde is important, if not necessary.

It seems nearly impossible for the avant-garde to thrive within today’s climate, especially in New York City where the conditions seem so disabling. Inequality runs rampant in both the art world and society, where the big fish eat the small fish, where the “shit rolls downhill.” The cultural climate seems so fragmented. At one part of the spectrum, there seems to be such a cultural focus on peddling very commercial merchandise, and then on another there’s that type of art world made to enlighten an audience that already considers itself self-enlightened. The latter is not only intellectually dishonest—it’s downright stupid. Both such elements should go into the dustbins of art history. I’m simply not interested. NYC is so expensive, and its culture is always on the brink of becoming so weirdly corporate that I sometimes wonder if art is continually losing its freedom here.

This is why I represent the artists I do at the gallery, whether it’s Maryam Jafri’s “war on wellness,” questioning the wellness-industrial complex in America; Pedro Wirz’s investigations into the possibility of a harmonious world of techno-organic ecology after apocalypses; Zoe Pettijohn Schade’s uplifting of women textile factory workers from the 19th century as great artists which were then applied to her meticulous gouache paintings exploring realms of labor and madness; Craig Kalpakjian’s demonstrations of surveillance and social control resulting in emptiness before a work is either in front of you or moving; Elliott Jamal Robbins’s investigations about the intersection between minstrelsy, cartoon illustrations, and sexual power; or Steffani Jemison’s engagement with literacy, the black vernacular, universal semantics, and mark making. They all tease me. They all embody such a spirit in their own way in this time as manifested in their art. Time will tell. Simply continuing the spirit, pursuit, and vision of questioning and experimenting are their defining hallmarks, and that’s true with all the above-mentioned artists. Philip Metten installation at Kai Matsumiya, 2015. Photo courtesy of Kai Matsumiya.

Philip Metten installation at Kai Matsumiya, 2015. Photo courtesy of Kai Matsumiya.

"WHAT I LOVE ABOUT THE ORIGINATION OF THE GRAMERCY INTERNATIONAL ART FAIR WAS THAT SMALL GALLERIES DECIDED TO SAY, 'TO HELL WITH IT, WE’LL DO OUR OWN THING!'"

—KAI MATSUMIYA

EC: The contemporary art industry has changed tremendously—both in New York and internationally—since The Armory Show’s launch in the mid-nineties. What are the biggest challenges you face as an emerging gallery today?

KM: The number one obvious answer, at least based on probable consensus, is that it’s financial pressure, if not survival, which represents the greatest significant challenge. However, that’s insufficient to me. There are more things than the purely economic. It’s also cultural. There’s also another type of unacknowledged pressure that’s afflicting us: peer pressure. What I love about the origination of the Gramercy International Art Fair was that small galleries decided to say, “to hell with it, we’ll do our own thing!” I try to muster as much will power as possible so that I may avoid any type of activity that’s ultimately predicated on peer pressure—about what art to show, what validating consortiums to join, who to be validated by. Succumbing to peer pressure results in a type of art that’s somewhere between forgettable and an afterthought.

EC: Which gallerists or galleries (past or present) do you look to for inspiration? Do you have any mentors whose ethos guide your decision making at the gallery?

I could name a number of gallerists that inspire my own gallery. The first inspiration is Liz Koury. I wouldn’t just call her a type of “mentor,” but really a type of “guardian.” She was the proprietor of International with Monument (est. 1983), Koury-Wingate, and later Liz Koury Projects. She’s one of the most important living and breathing gallerists. Nearly all her artists must be reckoned with if we are to understand contemporary art and the “avant-garde.” I’m not in the business of spouting off her professional and cultural accomplishments, but if you don’t know her, then do your homework. She represents the heart, soul, and strength of the art world. Pedro Wirz, Untitled: Haus/Nest, 2020. Photo courtesy of Kai Matsumiya.

Pedro Wirz, Untitled: Haus/Nest, 2020. Photo courtesy of Kai Matsumiya.

"EXPERIMENTATION FOR ITS OWN SAKE MUST BE CELEBRATED, BUT I DON’T THINK “SUCCESS” AND “FAILURE” MUST NECESSARILY BE ATTACHED."

—KAI MATSUMIYA

EC: You have been ambitious and unconventional in your programming choices, for example, staging eleven solo exhibitions in February of 2016. What experimentations have proven most successful and what failures have been the biggest lessons for you?

KM: Let me take a step back if I may. I tend to be fairly philosophically oriented outside of considerations of style. Experimentation for its own sake must be celebrated, but I don’t think “success” and “failure” must necessarily be attached. I often think about John Dewey, who was a utilitarian philosopher of education. He made a proclamation about how it’s impossible to know a truth unless it’s already happened, particularly in our modern condition in which new truths are happening all the time. He therefore posited how necessary it was to encourage experimentation in order for us to be more enriched, educated, and good willed. But to be sure, the truth itself must have happened. If we don’t seriously consider history, then what would appear as a new truth is in fact incorrect. We must challenge ourselves with healthy skepticism. The words “success” and “failure” are detached from “experimentation” in this way, and, besides, I don’t think of success and failure as exact opposites. If a show fails to generate significant attention and doesn’t sell, does that mean it failed? Ridiculous. Experimentation is for its own pursuit, and there’s no way it can be divorced from art.

In the most fundamental sense, showing a new artist is always experimental.

EC: Your booth at The Armory Show will be a solo presentation of Brazilian artist Pedro Wirz. Can you tell us more about the artist’s practice and why you chose to highlight Pedro’s work at The Armory Show?

Installation view of Pedro Wirz's exhibition "Breastfed Tadpole", 2018. Photo courtesy of Kai Matsumiya.

KM: Absolutely. Pedro Wirz will show a series of wall reliefs and sculptures. These works are wrought using materials found in nature such as rocks, soil, beeswax, and wood, integrated with manufactured elements like toy cars, plastic, and human-made debris, often from an imagined perspective of a child whose information is sourced from storytelling—mythological, symbolic, rumors, conspiracies, historical accounts. Such accounts represent the rational, irrational, and hyper-rational. If the world were to end by some major, man-made environmental catastrophe, and if new types of life forms can really emerge, Pedro proposes possible manifestations with his art making, as if the natural cosmos were hitting the “reset” button. That’s why, for example, we’ll be putting in “office” carpet at the booth. That “office” carpet will serve as a type of universal nourishment, like soil or the ocean, for the art works that “grow” out of it, so to speak. Under the carpet will be soil, so walking over it will create a wobbly experience.

For me, Pedro’s art, both in terms of its material and its ideas, are unique. I love it when people point out that they haven’t seen anything like it before. That gets me thrilled! Installation view of Pedro Wirz's exhibition "Breastfed Tadpole", 2018. Photo courtesy of Kai Matsumiya.

Installation view of Pedro Wirz's exhibition "Breastfed Tadpole", 2018. Photo courtesy of Kai Matsumiya.

"MY AIM IS TO CONSTRUCT A PLACE WHERE ANIMALS, PLANTS, MAN, AND MACHINE CAN COEXIST."

—PEDRO WIRZ

Molly Krause: Pedro, can you tell us in your own words a little bit about your presentation in Kai’s booth this year?

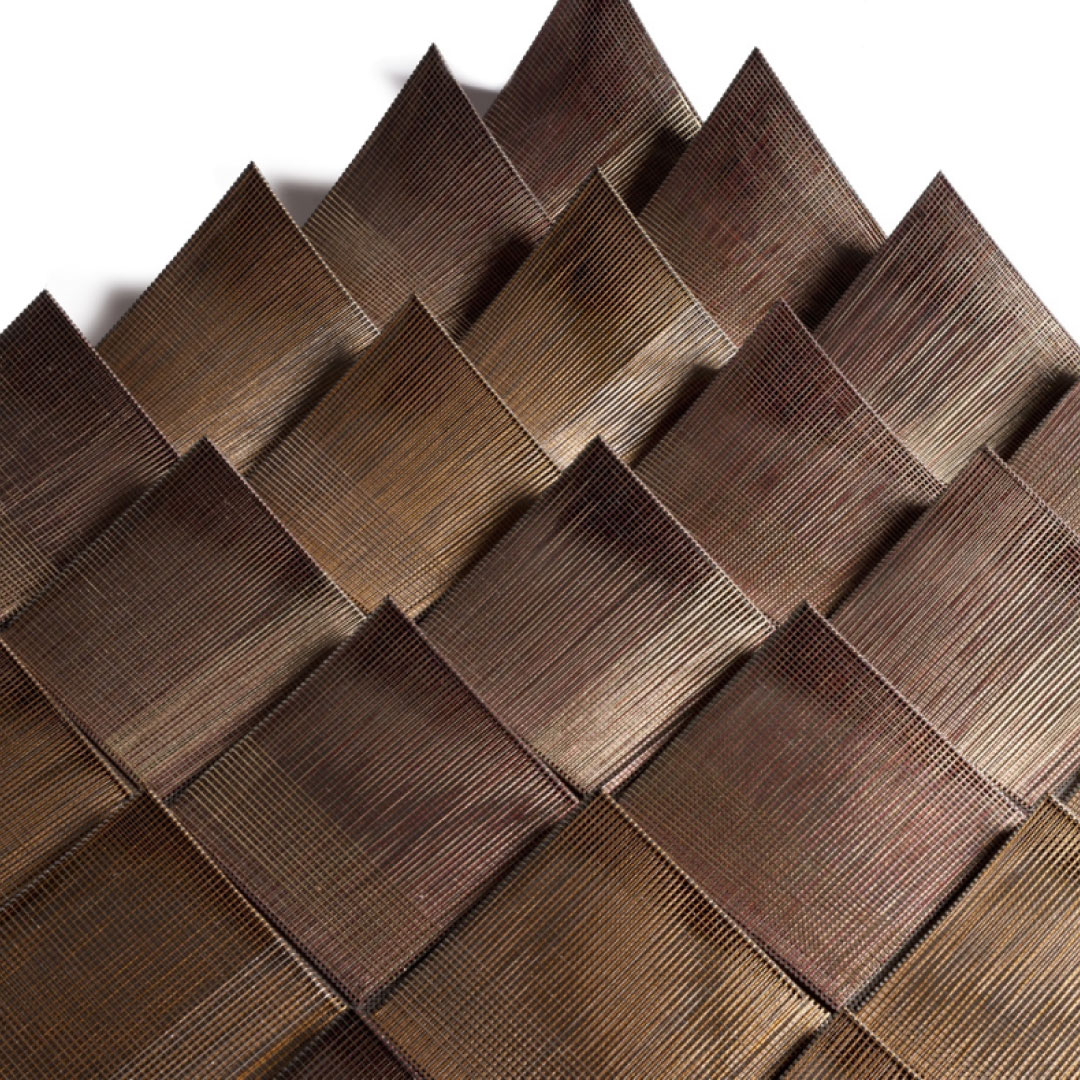

Pedro Wirz: My presentation for Kai’s booth will consist of five new works—four wall reliefs and one sculpture. Building on themes I initiated last September in my solo exhibition at Galerie Nagel-Draxler in Berlin, I am proposing a peaceful discourse between the rational, irrational, and super-rational worlds. My aim is to construct a place where animals, plants, man, and machine can coexist.

Pedro Wirz, Entsprechung VI, 2020. Photo courtesy of Kai Matsumiya.

MK: Can you shed some light on how your upbringing in Brazil and Switzerland influences your practice?

PW: It’s hard to define and measure which side of my cultural education plays a bigger role here, but I grew up in very close contact with the natural world in Brazil, and later moved to Europe to study in a Swiss Art School. I think adjusting to this dichotomy allowed me to appreciate paradoxical contexts, both in terms of my work manners and my aesthetic sensibilities. I like Swiss precision, but I love Brazilian spontaneity. Furthermore, I am the son of an agronomist (who worked with soil), and a biologist who conducted research on the influence of polluted water on DNA alteration, but I grew up in a region ruled by lore and popular beliefs—my work traverses these territories and seeks to merge the supernatural with scientific realities.

MK: You’ve shown your work in many different venues and contexts. Can you describe your experience exhibiting with Kai specifically, and the evolution of your gallerist/artist relationship since you were first introduced?

PW: I met Kai in 2014 through an artist friend of ours, and former teacher of mine, Rainer Ganahl. We worked together for the first time one year later on a group show at Kai’s gallery, organized by Rainer. The first time I heard Kai talking about my work to a visitor of the exhibition totally convinced me that this was a person I wanted to work with. Kai is a very sensitive and well-informed person within the art world—not a very common case among young dealers. We’ve been involved in many different projects since then, and Kai has helped me significantly—from editing grant proposals to securing my representation by other galleries (blank projects in South Africa and Nagel-Draxler in Germany). Many things have changed since we first start to work together. I've done two exhibitions at Kai’s gallery: The Horse Who Drunk Beer in 2016, and then Breastfed Tadpole in 2018. I think both of us are maturing into more professional roles, and, more importantly, our friendship has grown stronger. I am super excited about my third show at his gallery, opening this year during Armory week, titled Sour Ground.

MK: What have been your career highlights so far and what are your specific goals?

PW: I feel very lucky that each year after I finished art school (in 2011) has treated me differently and better than the one before. My institutional highlights have been showing at Kunsthalle Basel (2011), Künstlerhaus Stuttgart (2012), Dortmunder Kunstverein (2013), Palais de Tokyo (2013), CCS Bard Hessel Museum of Art (2015), Sculpture Park Cologne (2017), Instituto Tomie Ohtake (2017), Centre Culturel Suisse (2019), Kunsthaus Langenthal (2019), and Kunsthaus Aarau (2019). My main goal is to keep on working, to improve upon the use of materials I have chosen, and to bring the discussions I pose with my work to a broader audience. But to be very specific here, I wish to have an institutional show in the US in the near future—let’s see how that goes after my presentation at The Armory Show.

This interview has been edited for concision and clarity. Pedro Wirz, Entsprechung VI, 2020. Photo courtesy of Kai Matsumiya.

Pedro Wirz, Entsprechung VI, 2020. Photo courtesy of Kai Matsumiya.